When he died, things changed. People like Slobodan Milosevich began to harp on Serb Nationalism. He had his counterparts in Croatia, Bosnia, Montenegro and the other sub-states that had once enjoyed a reasonable prosperity as Yugoslavia. Manipulators of media began to play with memory, revise history. It's so easy when, like the Milosevich family, you have a near-monopoly on TV, radio, film and print.

I had the germ of an idea for a novel. I would create an alternate world, an earthlike place with technology at pre World War One levels. I don't know if this can be called a fantasy novel.

It has no wizards and very little magic. It just is what it is, an Alternate World. In this world, called Freeth, there are different geographies which lead, in turn, to different political destinies. I worked at the craft of what is called World Building.

This novel has gotten so huge that I now see it as a series of books, with a prequel and a sequel. So begins THE SHADOW STORM: BOOK ONE. I will post a few chapters and see if I can draw any readers.

The Shadow Storm

By Art Rosch February ã18,

2014

“In

the mists, there are unseen friends.

And in my friends, there are unseen

mists.”

From the

Matanyata of Raya

A Little History

A

statesman is a rare creature. The term

"statesman" evokes an aura of moral authority, gravitas and

self-sacrifice. Occasionally someone

arises who uses power for unselfish purposes, or yokes himself to higher

goals. This is a statesman.

Osskar

Skolov, President of the fledgling Kesh Republic, was a statesman. Even his enemies granted him that

stature. He had spilled plenty of blood

but he had never betrayed a friend and he always did what he said he would

do. A man of power who keeps his

promises earns respect all over the world.

Osskar

had united the many warring fiefdoms of the peninsula called Keshicstan. The multiple histories of Keshicstan differ

in detail depending upon who is telling them.

The four Nations of the Kesh have vied with one another for thousands of

years. Skolov's dream had been to unite the fractious tribes of the Kesh into a

political whole. It took arduous

struggle but he had succeeded in forging a new State. The Kesh Republic endured; a single generation had now passed.

The Republic was twenty eight years old.

It was a united Keschicstan's first democratic form of government.

Some

hoped for the republic’s collapse.

Among them were reactionaries from what had become the Four

Autonomies. They wished for a

restoration of their ancient empires.

These empires were mostly imaginary.

The only true chord of history running the length and breadth of

Keshicstan was one of raids and blood feuds.

The

nations who occupied Keshicstan were like four fingers runninng up the Kesh

Peninsula from the Vorget Ocean to the towering ranges of the Sarkadian

Mountains. The four nations, now called

The Four Autonomies, were the Kumysh, the Paltysh, the Lobanski and the Drugestni.

The animosities among the Kesh were fueled

by tribalism, religion and greed. Blood

feuds still raged among the clans in the mountains. Bickering between followers of The Adoration, The Schism and the

Goom were always spilling rivers of blood. Yet the tireless efforts of Skolov

and his inner circle had bonded these ancient rivals into a modern

republic. Now menaced by huge empires,

the Kesh were more frightened of the Klute, the Reverence and the Triple Culture

than they were of each other. There

were still terror groups plotting to

restore the "Old Kumyshia" or whatever state was being touted by

their revisionist historians. The

rational Center, federalists and republicans, wished desperately that the

fringe elements would disappear.

They never

did. Crazed longings for the days of

the Paltysh Empire, or the Drugestni Kingdom, haunted the political landscape

of the Kesh like the stink from an old paint job.

Osskar

Skolov had played upon these fears and suppressed these false memories, bandying

his motto everywhere: “Solidarity is

Survival.”

Skolov

had begun life as a simple soldier. In

the immense eastward reaches of the powerful Klute Hegemony, a civil war had

raged between followers of the two ‘Glavniks’, the hereditary rulers of the Klute. Prince Igor was the son of Glavnik Pyotr,

and he claimed succession when his father was poisoned. Prince Iossip was Igor’s uncle, and was

widely accused of doing the poisoning.

Uncle and nephew split the Hegemony into the White and the Purple Klute and

war had raged across a continent.

Osskar

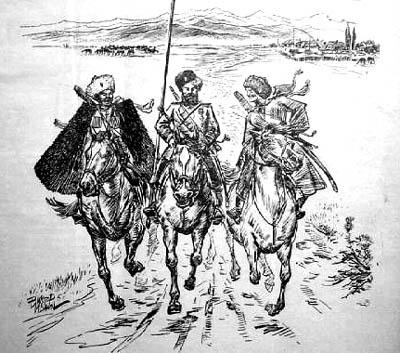

Skolov had been leader of a band of Kesh Comitadji. This term, Comitadj, attaches itself to young men from the

mountains who take up the life of nomadic mounted warriors. In the traditions of the Kesh, a Comitadj

becomes a protector of the powerless in times of invasion and oppression. Various governments utlilize bands of

comitadji in time of war as guerillas and scouts. They are mounted privateers of the border regions, for sale to

the highest bidder. In times of peace

they are bandits; in times of war they are heroes.

Osskar Skolov sold

his services to Igor, and it was Igor who won the civil war, to become the new

Glavnik.

Skolov,

however, built a mobile and powerful army around his core of fierce Comitadji.

In the confused aftermath of the civil war he managed to wrest the Kesh

Peninsula away from the influences of all its sponsors and oppressors. By doing so, he had turned the very

geography of Keshicstan into an economic threat pointed at the hearts of the

great empires. The peninsula is shaped like a bulb, with its socket screwed

into the Sarkadian Range. In the north,

the land butts into the Glazrov sea.

This narrow choke point is called The Bolkar Strait. At its narrowest point it is twenty four miles

across. On clear days one can see the

bluffs of the continent of Evra pushing into the sea like the paws of giant

lions.

When

the Klute civil war ended, the new Glavnik was filled with wrath. Igor scourged his officer corps, impaled

hundreds of his advisors, butchered the peoples of whole cities that he

considered disloyal. None of these savage measures could prevent a new Kesh

Republic from being established. Igor

wanted Keshicstan! It was a natural

extension of the Klute lands, the westward terminus of the continent of

Tauernoy. If he controlled the

peninsula, he controlled the Bolkar and

Skora Straits. If he controlled the

Straits he could strangle the entire world. He had anticipated an expansion

into the Peninsula, but the war had exhausted his treasury and decimated his

armies.

He

was not the only monarch on Freeth who wanted the resources and the strategic

advantages of dominating the lands of the Kesh. Every nation with a powerful army cast its eyes on Keshicstan,

planning and waiting.

In

the meantime, for twenty eight years, Osskar Skolov had held a precarious

balance, fending off enemies from both within and outside his very important

Republic.

One: Commander

For some months,

Anton Shariev was afraid that his boss was losing his mind.

One

day Osskar Skolov arrived at work wearing sporting clothes, as if he were out

for a game of Holes. To everyone who

knew him, this was astonishing. Osskar

never appeared in public wearing anything besides his trademark uniform. It didn’t matter whether he was working,

hunting or dancing with diplomats' wives.

He wore a version of his uniform.

They were all of the same design. Only the fabrics and colors changed.

Skolov was totally identified with that

uniform. It consisted of an officer's

tunic, a a cylindrical cap of black lamb's wool and an over-the-shoulder style

of belt. The flared wings of his cavalryman's trousers were tucked into knee

high riding boots. Sometimes he

holstered a giant revolver that people called an “Osskar”. Seeing him dressed otherwise was

shocking. Osskar in his uniform WAS the

Kesh Republic.

Recently, Anton had seen a glassy-eyed mania

creeping into Skolov’s manner. His

behavior was becoming more and more odd, by small increments. Only someone who

knew Osskar well would perceive these subtle shifts; it took Anton some time to

admit to himself that the Great Man's mind was drifting off center. This filled him with dread. If Skolov's judgment grew clouded he could

destroy everything they had fought so hard to achieve.

Anton

was shocked when his friend appointed a Personal Historian. It just wasn't in Osskar's nature. It seemed utterly wrong, as if The Commander

had been overcome by an evil and capricious djinn. He was a man who knew how to laugh at himself, a man without

pomposity or grand pretensions. The

Historian, a dry professor by the name of Ruslam Jeloof, followed Skolov all

day long, listening to the Great Man’s stories. Anton had heard tidbits of these stories as he went about his

work. Lately he had discerned outright

lies, fabrications that weren't remotely necessary to add luster to the career

of Osskar Skolov. Meanwhile, Jeloof

took notes, which he later digested into a daily log. He read this log to

Skolov first thing every mornng.

Early

on the Tenth of Moricarry, Shariev was

to brief Skolov on the fortifications in the north. War was inevitable.

Sooner or later, the Klute armies

would come pouring through the passes.

The guns, the tunnels, the obstacles, would not stop the Klute but they

would slow them down while mobile Kesh columns converged on the major points of

penetration. That was the plan,

anyway. Much depended on the Triple

Culture's dreadnoughts bottling up the Glavnik's new navy as it attempted to pass

the Bolkar Straits.

Anton

Shariev, Minister of Defense, knew from long experience that war plans were

like blueprints for buildings that will shortly topple.

Skolov’s office

was modest. The windows looked onto the

south side of the Kavalanski Palace, where two rivers, The Droon and the

Sabich, flowed under the city's many bridges.

The walls held decorations and souvenirs from his career as a

Comitadj. Weapons and bombs from seven

failed assassination plots sat atop file cabinets and small tables. A pair of crossed sabers hung behind the

desk, their gleaming blades inscribed with the gnarled tree branch patterns of

Old Lobanski script.

The

boss’s work area was littered with official papers and folders tied with blue

and red ribbons. Skolov leaned back in his big leather armchair, feet on the

desk. The palace was virtually

deserted. Two of Osskar’s trusted

bodyguards, Kwerk and Ayatov, were posted just outside the door. Historian Jeloof was perched on a stool in

one corner of the small office, with a pencil dangling idly between two middle

fingers. Early sunlight split into

bands of light and shadow as it flowed through venetian blinds.

Shariev

entered this scene, running early, as usual.

Jeloof was about to read the notes from the previous day. Skolov was relaxed and smiling, his great

mane of silvery hair standing straight up from his wide brow. Shariev felt the palpable charm of his

leader. There was, however, something

alarmingly brittle about this man, on this day. With a feeling as though he had fallen down a mineshaft, Shariev

truly admitted to himself: he looks crazy. His smile is too broad, too

glowing. It isn’t the Osskar that I

know.

To

a less acute observer, this bouyancy would pass for magnetism. To Anton Shariev, it had a euphoric quality

that undermined Skolov’s natural gravitas.

At sixty, he looked forty. He

was known for his clarity and candor.

He had written nine masterful works on statecraft and military strategy.

He was both an intellectual and an athlete.

His shoulders were massive, bulging out of the sports shirt that he

should not be wearing.

This

may have explained why Shariev felt a tingle of subliminal alarm as he entered

the room. Skolov just wasn’t Skolov any

more. He wore spats, knee length socks

over puffy woolen sport pants, suspenders and a sports shirt. He lolled with his feet elevated on his

desk. His shoes were fixed with the

short gleaming steel spikes of Holes players.

Anton wondered briefly if he might be looking at one of Skolov’s

doubles. He dismissed the thought. Anton knew the real article.

With

his palms turned upward, Skolov gestured expansively when he saw his

friend. “Aha! Colleague Anton! You’re a bit early but it’s a pleasure to see

you, even with your long gloomy face."

He looked at the historian.

"The Worrier, that's what I call him." He turned back to

Shariev. "Always worrying,

especially in the morning. Look out the

windows, look at the world! The sun is

rising, birds are singing! Who cares if

the carrion eaters of the Empires are gnawing at our frontiers? This is a permanent condition. Call it our Hot Peace. Eh! That's

good! Hot Peace." He turned to make sure the historian was

making a note of this catchy term.

Jeloof was dutifully writing in his tablet.

Skolof

twined the fingers of his hands, turned them inside out, extended his arms and

cracked his knuckles with loud pops.

"Aah,"

he sighed. His hands had taken a fair

share of shrapnel. His right pinky

finger was lopped off at the first joint.

Scar tissue covered his palms.

"I

was just about to hear what Colleague Jeloof gleaned from yesterday’s

proceedings," said Skolov.

"Go ahead, read your notes."

“Sir,”

Jeloof said respectfully. “I have only

three paragraphs of notes. It was

an ordinary day. You spent three hours with Citizen Vridilov

discussing his difficulties in designing a workable flying machine. There's not much else of distinction beyond

your regular administrative duties."

The

smile on Skolov’s face disappeared. He

stood abruptly, using his body to push his chair backwards so that it hit the

wall with a padded thunk! He reached to

one of the pair of antique sabers and withdrew it from its clip on the

wall. He strode with exuberant purpose

to the side of the tall thin man with his pencil and clipboard. Terrified, Jeloof retreated into a corner of

the office, dodged forward, dodged back, slunk along the inner wall, but could

not evade his employer. Skolov stabbed

into the right cheek of Jeloof’s rangy buttocks. His raised voice sounded rough and splintered.

“There are no

ordinary days in the life of Osskar Skolov!

Maybe this will give you something to write about!”

There

was a shocked silence in the office.

This was an insane autocratic gesture in the style of some medieval

Klute despot like Igor the Awful.

Shariev stood there,

stunned.

Blood

spilled down the leg of Jeloof’s trousers.

The historian’s face went from pale to scarlet. He looked over his shoulder at the bleeding

wound and began to weep. His tears reminded Shariev of his own

adolescent daughter after a tiff with her boyfriend. Jeloof was standing directly beneath the other saber that hung

clipped to the wall. He then did the

unthinkable. He took the sword into his

hands and slammed it down on Skolov’s head with firm and utter finality. Osskar barely had time to raise the other

sabre to his waist before the fatal blow had fallen. The Commander had not considered the dry twig of a man to be

capable of holding a sword. He had not

braced for a counterstroke, he had simply stood panting, enraged. Now he was dead.

It

took about five seconds for Kwerk and Ayatov to enter the office, assess the

situation, and shoot Jeloof full of holes. They were so surprised, so numb with

shock that it was easy for Shariev to draw his own pistol and kill both

bodyguards. Kwerk died instantly with a

shot through the heart. Ayatov took a

bullet in the arm and a fatal shot in the temple.

Shariev

was now alone in the Commander’s office with four corpses. He was

deafened. Smoke filled the air and the

smell of discharged firearms burnt his nose.

He was thinking at incredible speed.

He could feel his pulse in his ears, and the walls of the room seemed to

twist and buckle for a moment. Shariev

deposited his shame, grief and terror into a remote vault in his psyche. It took great effort. There was no time to be emotional.

If

word gets out that Skolov is dead, murdered, the Kumysh will blame it on

everyone else and begin a secession bill in their legislature. The other Autonomies will follow suit and

street fighting will begin between the separatists and the unionists.

Keshicstan will implode and the empires will take advantage of the chaos to

invade from every quarter. These months

were desperately needed by the Keshic military to complete its

preparations. Without Skolov, there

would be no Army Of The Republic.

Skoloff commanded loyalty in his person as The Great Comitadj. He had Besha affliations with every

clan; every hetman in every peak and

valley owed a debt to Osskar. As Prime

Minister in the Demyat, Osskar was transferring loyalty piecemeal to the Kesh

Republic. It was a long and gradual

work. If he died without a strong

successor, officers and soldiers from the Four Autonomies would return to their

homelands and resume the blood feuds that had burned for a thousand years. Then Igor and The Klute would come flooding

through the mountain passes to pick off one army after another. Morthone Friedrich could not allow this to

happen. The Triple Culture and its

allies would be at war with the Klute and its allies, and all of Freeth would

be at war.

It

would be the first true world war on the planet. The largest battle would be for control of the peninsula,

Keshicstan. By the time it was over,

The Republic would be a wasteland.

Anton

opened the door carefully. It was just

past five in the morning. No one was in

the Kavalanski Palace. This baroque

monstrosity, residence of former Kings, had been converted into the hub of the

Republic’s government. A few janitors

patrolled the lower floors, stacking the furnaces with coal.

Anton

would now have to act with great cunning if he was to keep Skolov’s death

secret. He conjured a map of

deployments of all the military formations that would be involved in this

struggle.

The

Triple Culture, by treaty, would be obliged to defend the Kesh Republic. This defense could end up looking like an

occupation; if they came, the Morthone's troops would never leave. The Morthone’s navy was prepared to deploy

in an arc across the Bolkar Straits to blockade Klute shipping. This would force Igor's army to come across

the Sarkadian Range. But Friedrich's

fleet was only powerful on paper. Many

of The Culture’s dreadnoughts were berthed at Zyle Harbor for refitting. Shariev anticipated the emergence of a

viable aircraft, or an underwater torpedo boat. These things were in the works, still visions on the draft tables

of engineers and designers. This was a

time of innovation, many of which would be frightful.

In

a tangle of cross-alliances, as economic and historical grievances erupted,

twenty nations would soon be

fighting one another. Most of that

fighting would be around and within Keshicstan.

There

was a key to Skolov’s office in his desk drawer. Shariev found it and left the office, locking it behind him. He went down the corridor of what had once

been royal parlors and bedrooms, now utilized as offices. He found a supply

closet and extracted a large roll of brown wrapping paper and several rolls of

tape. He took a box of cleaning rags

under one arm and hurried back to the Commander’s office.

Working

frantically, Shariev cleaned up the blood, rolled bodies in carpets, opened the

window to air the smoke from the room.

Dawn was breaking over Kacedon’s spires and minarets. The Anwars were calling to Ayubah, the

Masters were ringing steeple bells and the Acolytes were sweeping burnt incense

coals in front of their iconostases.

Sweat

poured from Shariev’s body. He needed

time. Six months at least for the new

defense perimeters to be completed. The

Klute Civil War had been followed by the Independence War. Twenty eight years ago a vicious war had

been fought. It had never really

stopped. It had gone into remission,

like a cancer. Continual outbreaks and

alarms disturbed the repose of the continents Evra, Skora and Tauernoy.

The treaty of

alliance with Friedrich and the Triple Culture protected the new Kesh

Republic. It came with a heavy a

price. Tariffs had been lifted. Trade agreements forced Osskar to lay a

burden of heavy taxation on the citizens of the Republic.

In return, fleets

of dreadnoughts and cruisers flying the tricolor of Friedrichs’ realms

patrolled the Bolkar and Skora Straits.

They ranged up and down the coast of Evra and parried warily with their

de-facto enemy, the Klute Imperial War Marine.

As for ground forces, the Morthone’s divisions were still far away. If they came to the defense of the Kesh, it

would take weeks for them to deploy.

They might not come at all, if Glavnik Igor could break the blockade of

the straits. Then Igor could stall

Culture troop movements and send his client armies into the Culture’s vassal

states.

Time, time,

Shariev needed time.

He could not even

mourn the loss of his mentor and friend Osskar Skolov. He couldn’t indulge in the grief and shame

of being forced to murder Kwerk and Ayatov, loyal soldiers who did not deserve

such a fate. A spasm of emotion was

swallowed up in the moment’s urgency. He needed to restore the office. There were rugs in the storeroom. He must get two to replace the bloodied

shrouds he was now using to transport the bodies. He found what he needed, a large wheeled cart, and brought the

new rugs into the office. He moved

furniture, straining to shift the Commander’s massive desk a few inches at a time. Then he put the bodies on the cart and

rolled it to the service elevator.

There were four rug-and-paper wrapped bundles, six feet long, tied with

beige twine. The elevator rose with

infuriating slowness, groaning on its cables.

At last the chamber came even with the steel crosses of the folding

gate. Shariev grasped the handle,

accordianed the gate open, and clumsily moved the cart into the interior. It was now quarter till six. Within the hour, employees of the various

ministries would be arriving for work.

Shariev

pressed the button to take him to the basement, to the boiler rooms. The elevator clanked and creaked, shuddering

its way downward. The defense minister

mopped his brow with a clean rag. He

examined himself. He was covered in blood

and bits of bone. He would need

clothing. He took the minutes of

labored descent to think through his next moves. First and most obvious was to activate Skolov’s best double, a

man named Felix Birel. This man had

been surgically altered and trained for years. Shariev would have great need of

Birel in the coming days. He would also

need to contact the Chief of the War Staff, Iosef Surijatsky. He could confide in Iosef, but instinctively

he wanted to hide the truth for as long as possible.

To

the east, Igor the Fifth, “The Glavnik”, maneuvered and prepared his armies,

the forces of The Klute Hegemony. To

the southwest, across the Skora Straits, the Party of Reverence threatened the

Republic. Their military was second

rate, their equipment out of date.

Nonetheless, divisions had to be stationed to keep them from

landing. To the northwest, the Triple

Culture maintained its friendly ties with the Kesh only so long as it was

cheaper to buy from them than to conquer them.

If a power vacuum occurred on the peninsula, the three empires would

rush in like three great rivers, each waving the standard of its religion,

proclaiming war for the greater glory of whatever God happened to apply. No

matter that Friedrich was an ally. He

would bring his armies to “defend” the Kesh, and then never leave. None of the empires could afford to let the

other dominate the peninsula. The Land

of the Kesh was a geo-strategic fulcrum.

Part of the reason for Osskar’s success was the fact that so long as he

restrained the Four Autonomies and held The Republic together, a balance of

power obtained and the empires could relax.

None wanted any of the others to have Keshicstan.

This

armed stability could go on for decades, perhaps generations, but for one

obsessive ruler, Glavnik Igor. He

seethed with rage towards Skolov for thwarting his annexation of the

peninsula. It was a personal affront.

Osskar

Skolov’s very existence had acted as a dyke to hold back the tides of war.

Shariev

gripped the front of his waistcoat and tore at his lapels in a gesture of

agony. He needed some way to vent the

emotion that was being so tightly held in check. His fingernails dug through the black woolen material until they

scratched his ribcage. A silent sob

twitched his shoulders like a hiccup.

No more, no more,

he told himself. I can’t grieve

now. I have other things to do. Memories of Osskar flooded through him:

Osskar pretending to feel no pain as a bullet was removed from deep within his

thigh. Osskar laughing with his head

thrown back, a bottle of raki glinting in the campfire light. Osskar with his brows knit over a map as he

worked out escape from a hopeless encirclement. In spite of his attempt at self control, Shariev’s shoulders

trembled and he winced with the salt sting of tears. His face was filthy. The

lines of tears made clean narrow stripes across his cheeks.

Goddammit! This was a nightmare! A nightmare! Of all the things Skolov had done, and done wisely, he had

dallied over the most crucial: a smooth transfer of authority. He, Shariev, had urged this for years upon

the Commander. Who will succeed you? he

implored. What if something should happen? The Constitution provided, upon the loss of

a Prime Minister, an interim government headed by the Cabinet, with Shariev as

its de facto head. After a period of

ten weeks, a general election would be held.

During that ten weeks, all registered parties would campaign, form

coalitions, jockey for position, and the resulting party or coalition with the

greatest number of elected representatives to the Demyat would establish its

leader as the new Prime Minister. As

things stood right now, the next Prime Minster would be the industrialist Zemso

Borenko. This revanchist lunatic was a

Kumysh, and behind his rhetoric of reconciliation hid the old dream of

secession and Kumysh grandeur. His

policies would lead to invasion, disintegration of the Republic, and a wider

war over the carcass of the peninsula.

Osskar

could not let himself believe in such an outcome. He would laugh and flex his shoulder muscles, stretching the

fabric of his tunic as if to demonstrate his excess of vitality. “Anton, there’s time. Who can succeed me? Be realistic! Who! There IS no other

Osskar Skolov. I’m going to have to

create one! And I haven’t found the

proper clay, as yet. I’m not god, I

can’t make a successor out of nothing.

You don’t want the job! Neh? You are a behind-the-scenes type. Maybe…maybe, if Surijatsky were less

eccentric, I could see it. But no…..we

must wait. There is time. Borenko is nothing but a joke, yes, a

dangerous joke, but it would take a lot to bring him to power. I have my eye on young Vlahos. I know, I know, he’s a stripling! But I see the potential in him. Think about it. Another five years and young Alyosha’s beard will start to have

some grey in it. Then he will be taken seriously by the old Comitadji.”

In hindsight

Shariev understood that a mental illness had laid hold of Osskar. It had come slowly at first. In the last two months things had accelerated,

the Commander’s behaviour had become subtly out of tune. How little was understood about the

mind! A new science was emerging,

Psychodynamics, but it was still primitive.

What could he, Anton, have done?

His mind swung wildly with strange emotion. Could I have suggested that Osskar see Professor Zuring and go

into treatment?

The

thought was so absurd that he laughed with his mouth closed, and a cloud of

snot dripped from his nostril and spread through his moustache. He wiped his face with the rag he held. Perhaps I need a few sessions with the

doctor myself, he thought miserably.

The

elevator settled with a bump. Shariev

slammed the screen aside and rolled the cart out into the subterranean vastness

of the Kavalanski Palace.

There

were pillars receeding into the smoky distance. A caged gas light shone feebly, every twenty feet. This part of the palace had not yet been

electrified. There was a rumble, as of

machinery, furnaces, vents being opened and closed. There was no complete map of the palace’s subterranean

layers. It was riddled with tunnels,

legacy of Kavalanski paranoia. Anton

set off towards a sound of muted roaring, seeking the heat of the great

boilers.

He

got about fifty yards when a convergence of two walls became a corridor. Only a few paces down this corridor there

was a steel door. It was slightly

ajar. He looked through into a spacious

chamber, lit with kerosene lamps, fitted with a spider of colossal vents

working their way up into the palace.

He saw an old man seated on a stool, smoking a pipe whose stem was so

long that its bowl rested on the floor.

Next to him, a vast pile of coal rose to the ceiling. A giant furnace roared behind its closed

iron gate at the far side of the chamber. The man wore the white skullcap of a

Lobanski Mountain Man. This spectral

figure looked up and met the eyes of Anton Shariev. He rose, lifting the pipe with him, leaning it against a niche

where old furniture lay stacked.

The

man was tall, with a face like a predator. A sparse beard of white stubble covered his chin and upper

lip. He touched a finger to his

skullcap respectfully, but without subservience. “Minister”, the man spoke, “what are you doing here?” He

approached Shariev, walking with a pronounced limp. Anton did a lightning assessment. This man was a Lobanski, displaced from his mountains and his

flocks, serving as a janitor in the Kavalanski Palace. He had fought bravely, saved someone’s life

in his career as a bandit, a Comitadj.

As his reward he had been given a sinecure, a job in the palace, an

apartment and a stipend.

Shariev

would have to bestow his trust on this man.

He rolled the cart through the door.

“There has been some difficulty,” he explained vaguely. “I need to burn these parcels.”

“Certainly,”

the man rumbled. His voice had the

thickness of one who speaks little. He

examined the trussed beige packages, and his nostrils opened and closed, opened

and closed. Shariev knew the man

smelled blood.

“Difficulty

indeed,” the Lobanski said sardonically, darting a keen glance at the

minister. He displaced Shariev at the

handle of the cart and rolled it towards the furnace. “You need to dispose of some awkward refuse.”

Gratefully,

Shariev let the man take the burden..

He mopped his brow once more then joined the janitor at the door to the

furnace. The man opened the

wrought-iron hatch. It gave a poignant

squeak and revealed its well-tended and relentless fire. In the light of the flames, Shariev’s torn

and bloody clothing was visible,. The

hill man looked him up and down, shrugged, and pulled at the first

package. Shariev felt a dreadful sense

of lese majeste, that he was consigning the Commander, the Leader of the

Solidarity, to an anonymous furnace fire, that the Prime Minister's smoke would

go up and out the chimney of the Kavalanski, that the heat from his bones and

tissues would be distributed to a hundred radiators heating a hundred

rooms.

The

old Comitadj lifted one end of the first bundle, and Shariev took the other

side. Together, they fed it into the

flames. Indifferent to its fuel, the

furnace roared briefly, then settled to its steady crackling.

Before

Shariev could designate the second rug-wrapped tube, the old Lobanski pulled at

the one containing Skolov. It was damp

with blood, and part of the paper ripped, revealing a hand. The hand was uniquely distinctive. It was missing part of its little

finger. Its old cuts and burns belonged

to one man and only one man and that man was famous enough so that his hand

told his identity.

The

janitor dropped the package back onto the cart, and in a swift and practiced

movement pulled a dagger from his belt

and held its gleaming blade to the throat of Anton Shariev.

“I

want to know what’s going on here!” the man bellowed. “I invoke K’nuun. Why is the President’s body being fed to the

furnace? Who has killed him!”

The

K’nuun was the ancient tribal code of the Kesh, an oral tradition that every

Kesh male learned from birth. To invoke

K’nuun meant that one of two responses was demanded: the absolute truth, or,

the phrase “The K’nuun is not within reach.”

The latter was only permitted if the truth put the speaker’s family in

danger of blood revenge.

Slowly,

Shariev raised his right hand and held it under the Lobanski’s nose.

“Do

you smell gunpowder?” he asked. The

blade's point was drawing blood from the area near his jugular.

The

Lobanski nodded. “Gunpowder. Go ahead.”

“The

President was killed by a sword. His

bodyguards killed his killer, then I killed his bodyguards. It’s gruesome, but you can examine his body

and see if I speak true.”

The pressure on the blade slackened. The old mountan man thought for a moment. “I see. You must keep the President’s death a secret. He is the only man who commands the loyalties of all the Autonomies. If his murder is made known, the Republic is weakened and becomes fair game for the Empires. And the Empires have been rattling their sabers, itching to get back into a war.”

The pressure on the blade slackened. The old mountan man thought for a moment. “I see. You must keep the President’s death a secret. He is the only man who commands the loyalties of all the Autonomies. If his murder is made known, the Republic is weakened and becomes fair game for the Empires. And the Empires have been rattling their sabers, itching to get back into a war.”

The

dagger came away from Shariev’s throat.

By the flickering light, the Defense Minister saw the old man straighten

his body proudly, draw himself up to his considerable height.

“Then

I must die too,” he said, smiling broadly.

“I could give you my word to keep this secret, but we both know that

secrets are like blood: they appear at the first scratch. I will die for the

Kesh. Not for the Republic. Excuse me, sir, but the Republic can screw

itself. I’m too old to change my

ways. I am a Lobanski first, a Kesh

second. This is a far better death than

I had hoped. Even my grand-daughters

have been taunting me: ‘grandpa, why

are you still alive?’ I have outlived

most of my sons and even some of my grandsons.

I am stoking a furnace, exiled from my flocks, my horse and my saber,

because of a war wound that never healed.

You have brought me a good death, worthy of a Comitadj.”

Shariev

stepped back from the heat of the fire.

“You will die a warrior, and when it can be known, I will add your tale

to your Besha’s K’nuun. I will see to

it that your family is cared for.” The

Besha was the man’s clan affiliation.

The

Lobanski examined Shariev. “You are of

my size. You will need my clothes. I

will go into the furnace at the side of Osskar Skolov. He was a great man, the greatest of the

Comitadji.”

Shariev

sagged into the man’s arms with exhaustion and relief. “You are my brother,” he wept into the

Lobanski’s bony shoulder. The Lobanski

wept back, squeezing him tight.

“You are my

brother in the K’nuun. Let us

respectfully cremate the Commander and then you can slit my throat and make

steam of my blood. My smoke will mingle

with The Commander's smoke.”

Before

enacting the ritual death of the Lobanski, Shariev became his brother. He

learned his name, his tribe, his clan, his Besha, and the man learned that of

Shariev. The old warrior, whose name

was Leet Krvash, showed Shariev a tunnel out of the palace of which he had been

unaware. It would take him to a decayed

gazebo in Vronsky Park, where he could slip quietly into the city.

Krvash shed his

clothes. He stood proudly in his faded

set of long johns. He washed himself in

a bucket of warm water, took one final drag from his pipe. He looked exultant. He wept with joy.

“This

is a death that means something! I

thought I would rot here, getting so old that I would not be able to straighten

my limbs, and then my daughters would lay me on a bed in my village and smother

me in my sleep. Which is only

proper! I would have been an

embarrassment! This is a unique death:

a warrior’s death.” He knelt on a great

pile of rags gathered from around the boiler room. Shariev, too, had shed his clothes and put them into the fire,

along with the bodies of Kwerk, Ayatov, Jeloof and Osskar Skolov. He circled behind Leet’s back, grasped his

forehead but refrained from pulling the head back or touching the hair. That was not the way to slit a throat. He allowed Leet Krvash to adopt the Pride

Posture, The Warrior's Way. When the

man was set, Anton passed Leet’s blade across his throat. The blood flowed like an apron across the

Lobanski's torso. It spilled onto the

rags. Leet Krvash sighed, dropped to

his knees and fell forward.

Shariev

fed him into the flames with the prayer called The Cry For Redemption, from the

Schismatic Rite. When it was all done,

everything cleaned up, he donned the clothes of Leet Krvash and went down the

long, fetid tunnel that led from the Kavalanski Palace.

He

wondered, as he cautiously pushed up the planks of the gazebo’s floor, how many

more people he would have to kill with his own hands before this horrible

business was done.